Associative play represents a critical milestone in early childhood development when children transition from playing alongside peers to genuinely engaging with them. For preschool educators and administrators worldwide, understanding this developmental stage is essential for creating environments that foster healthy social, emotional, and cognitive growth.

According to the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC), play-based learning forms the foundation of quality early childhood education. This comprehensive guide explores associative play’s role in child development and provides practical strategies for implementing it in your preschool program.

What Is Associative Play?

Associative play is the fifth stage in sociologist Mildred Parten’s widely recognized framework of play development, first published in 1932 in the Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. During this phase, typically occurring between ages 3 and 5, children begin actively interacting with peers during play activities. They share materials, exchange ideas, and show genuine interest in what others are doing—yet they maintain individual goals rather than working toward a unified objective.

Unlike parallel play where children play side-by-side without interaction, associative play involves verbal communication, spontaneous conversations, and material sharing. However, it differs from cooperative play in that children haven’t yet developed the ability to assign roles, follow shared rules, or work systematically toward common goals.

Key Characteristics of Associative Play

Social Engagement Without Formal Structure

Children actively talk to each other, ask questions, and comment on peers’ activities. You’ll hear phrases like “I like your tower!” or “Can I use that block?” However, there’s no predetermined storyline or coordinated plan. Research from Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child demonstrates that this unstructured social interaction builds crucial executive function skills.

Flexible Material Sharing

Children freely exchange toys and supplies without formal turn-taking systems. One child might hand over a paintbrush, while another offers crayons—all without explicit negotiation. This spontaneous sharing is markedly different from the resource guarding typical of earlier developmental stages.

Parallel Themes, Individual Execution

Two children might both build structures with wooden unit blocks, discussing their creations enthusiastically, yet each constructs something entirely different with no shared blueprint. This simultaneous independence and interaction characterizes associative play.

Emerging Social Awareness

Children demonstrate growing empathy by noticing when peers are upset, celebrating others’ achievements, and beginning to understand social dynamics. The American Academy of Pediatrics emphasizes that these early social-emotional skills directly predict later academic success and mental health.

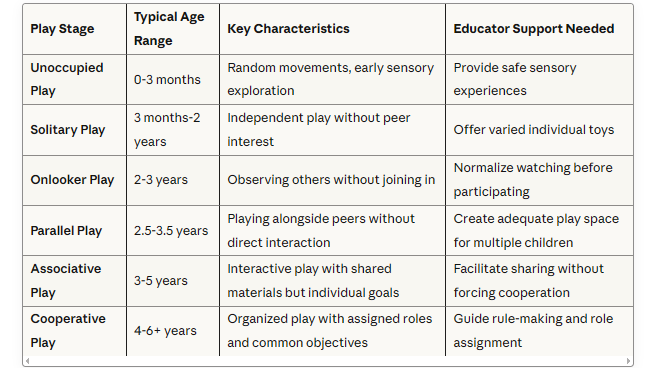

The Six Stages of Play Development

Understanding where associative play fits within the broader developmental framework helps educators provide age-appropriate activities and realistic expectations. This progression, outlined by Parten and expanded by contemporary child development experts at Zero to Three, shows how social skills gradually emerge:

Most children progress through these stages sequentially, though individual timelines vary significantly based on temperament, cultural background, and prior social experiences.

Why Associative Play Matters for Preschool Programs

Cognitive Development Benefits

Problem-Solving Foundation

When children encounter conflicts over materials or space during associative play, they develop critical thinking skills essential for academic learning. Research published in Early Childhood Research Quarterly demonstrates that unstructured social play significantly enhances executive function development, including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control.

Language Acquisition Acceleration

The spontaneous conversations during associative play create rich language-learning opportunities. Children expand vocabulary, practice sentence construction, and learn conversational turn-taking organically. For multilingual classrooms, associative play provides natural contexts for language development across cultures.

Mathematical and Spatial Reasoning

When children discuss building projects or compare creations during associative play, they naturally engage with mathematical concepts like size, quantity, symmetry, and spatial relationships—all critical for later STEM learning.

Social-Emotional Growth

Empathy Development

Associative play provides the first real opportunities for children to recognize and respond to peers’ emotions. This lays groundwork for emotional intelligence that extends into adulthood. The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) identifies peer interaction during play as a core mechanism for developing social-emotional competencies.

Conflict Resolution Skills

Without adult-imposed rules, children learn to navigate disagreements independently—a crucial skill for school readiness and lifelong relationship management. Educators should resist over-intervention, allowing children to develop negotiation strategies naturally.

Friendship Formation

Early peer bonds formed during associative play often become foundational social relationships, building children’s confidence in group settings. These early friendships teach children about loyalty, shared interests, and mutual support.

Physical Development

Fine Motor Skills Enhancement

Manipulating wooden puzzles, building blocks, and art materials during associative play strengthens hand-eye coordination and fine motor control essential for writing readiness.

Gross Motor Coordination

Playground equipment, climbing structures, and physical games during associative play develop balance, coordination, and body awareness while children interact with peers.

School Readiness Outcomes

Studies consistently show that children who engage regularly in associative play demonstrate:

- Better classroom adjustment and reduced separation anxiety

- Increased focus during structured academic activities

- Stronger collaboration skills during group projects

- Higher levels of creative problem-solving

- Greater emotional regulation during transitions

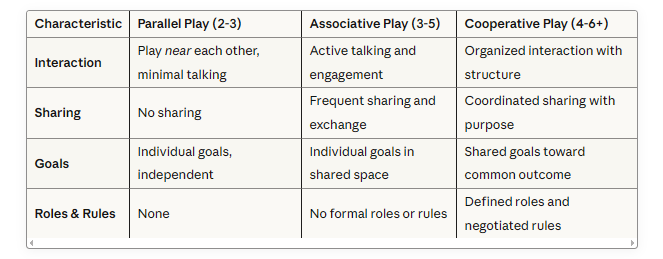

Associative Play vs Other Play Stages: Understanding the Differences

Associative Play vs Parallel Play

Many educators struggle to distinguish between parallel and associative play, as they appear similar on the surface. Here’s the critical difference:

Parallel Play (Ages 2-3):

- Children play near each other with similar toys

- Minimal or no verbal interaction

- No sharing of materials

- Complete independence in activity execution

- Limited awareness of peers’ activities

Associative Play (Ages 3-5):

- Active verbal communication between children

- Frequent material sharing and exchange

- High interest in peers’ activities

- Individual goals within shared space

- Spontaneous conversations about play activities

The Key Distinction: In parallel play, children are aware of each other but not engaging with each other. In associative play, active engagement occurs without coordinated goals.

Associative Play vs Cooperative Play

Understanding this transition helps educators support children’s progression toward more complex social interaction:

Associative Play (Ages 3-5):

- Loose, unstructured interactions

- No assigned roles or rules

- Individual objectives

- Spontaneous, fluid participation

- Sharing without coordinated purpose

Cooperative Play (Ages 4-6+):

- Organized with clear structure

- Defined roles (leader, follower, specific characters)

- Shared goals and objectives

- Negotiated rules and responsibilities

- Division of labor toward common outcome

The Key Distinction: Associative play involves interaction during independent activities, while cooperative play involves interaction toward a shared outcome.

Classroom Examples of Associative Play in Action

Understanding theoretical definitions matters less than recognizing associative play when you see it. Here are detailed scenarios from real preschool environments:

Art Center Activities

Scenario: Three children sit at an easel station stocked with wooden-handled paintbrushes and shared paint pots. One paints a rainbow, another creates abstract patterns, and the third works on a family portrait.

Associative Play Indicators:

- They share brushes naturally: “Can I have the thick one when you’re done?”

- They comment on each other’s work: “That purple is pretty!” “Your rainbow has lots of colors!”

- They occasionally watch what peers are creating, incorporating ideas into their own work

- Each completes their own unique artwork with no shared vision

What Makes This Associative (Not Cooperative): Despite frequent interaction, there’s no unified artistic goal or collaborative mural—each child’s artwork remains entirely their own creation.

Block Building Area

Scenario: Two preschoolers work with the same set of wooden unit blocks. One builds a tall tower while the other constructs a bridge.

Associative Play Indicators:

- Constant verbal exchange: “I need the big rectangle,” “Look how high mine is!”

- They hand blocks to each other: “Here’s a triangle you can use”

- They compare structures: “Mine is taller!” “But mine is wider!”

- They might temporarily incorporate pieces into both structures but maintain separate building projects

What Makes This Associative (Not Parallel): Unlike parallel play where children work silently side-by-side, these children actively communicate and share materials throughout the activity.

Dramatic Play Corner

Scenario: Children engage in dress-up activities around a wooden play kitchen set, putting on costumes and pretending to be different characters. One child becomes a doctor, another a chef, and a third a superhero.

Associative Play Indicators:

- They interact: “Can you help me with this cape?” “Do you like my hat?”

- They acknowledge each other’s roles: “The chef is making pizza!” “The doctor has a stethoscope!”

- They share props and costumes from communal bins

- Each maintains their individual character without a unified storyline

What Makes This Associative (Not Cooperative): They’re not acting out a cohesive story together (like “superhero saves the chef from the villain”). Each child independently develops their character while remaining socially engaged with peers.

Sensory Table Play

Scenario: Four children explore a sand and water table equipped with wooden scoops, boats, and funnels.

Associative Play Indicators:

- Each digs, pours, and molds independently while commenting on discoveries

- “The sand is really wet here!” “I found a shell!” “Watch this pour!”

- They pass tools back and forth: “Can I use the boat?” “Sure, here!”

- They observe each other’s techniques: watching how a peer creates a tunnel, then trying it themselves

- No coordinated building project emerges despite proximity and interaction

What Makes This Associative: The key is simultaneous independence (each pursuing own exploration) and interdependence (frequent sharing and communication).

How to Support Associative Play in Your Preschool: Evidence-Based Strategies

Classroom Environment Setup

Create Multi-Access Play Stations

Design activity areas that accommodate 3-5 children comfortably. This encourages interaction without forced cooperation. Research from the HighScope Educational Research Foundation demonstrates that optimal play areas provide:

- Clear boundaries (rugs, low shelving) defining space

- Adequate materials so sharing happens naturally rather than from scarcity

- Visual access to other areas, encouraging movement between activities

- Comfortable seating or floor space for extended play sessions

Choose Open-Ended Materials

Wooden toys excel for associative play because they invite creative interpretation without prescriptive use. Unlike battery-operated toys with predetermined functions, wooden materials allow children to pursue individual interests while remaining engaged with peers.

Our natural wooden construction sets are specifically designed for open-ended exploration, supporting associative play by:

- Offering multiple simultaneous uses (one child builds a house, another a road)

- Inviting language-rich descriptions (“I need the curved piece,” “hand me the red cylinder”)

- Requiring negotiation over limited resources

- Allowing creative transformation (a block becomes a phone, then a car, then a building)

Arrange Furniture for Visibility and Interaction

Position play areas so children can easily see peers’ activities. Research published in Environment and Behavior journal shows that classroom layout significantly impacts social interaction frequency:

- Use low shelving (maximum 36 inches) as area dividers

- Create open floor plans that facilitate spontaneous joining of activities

- Position mirrors at child height to increase awareness of peers

- Ensure adequate lighting in all play zones

Establish Predictable Routines with Extended Play Periods

Associative play requires time to develop. According to NAEYC’s developmentally appropriate practice guidelines, preschoolers need minimum 45-60 minute uninterrupted play blocks to:

- Settle into activities without rushing

- Initiate and respond to peer interactions

- Develop complex play scenarios

- Experience natural conflict and resolution cycles

Material Selection for Associative Play Success

Optimal Wooden Toy Choices for Different Activity Centers:

Construction and Building Area

- Unit blocks in various shapes (rectangles, triangles, curves, cylinders)

- Natural wood planks and boards of different lengths

- Connecting wooden pieces (pegs, interlocking systems)

- Stacking toys of different dimensions and weights

- Simple vehicles and figures for scale play

Why These Work: Multiple children can build simultaneously with enough variety for individual creations, while similar materials encourage conversation (“Where did you find that arch piece?”)

Pretend Play and Dramatic Play

- Wooden kitchen sets with accessories (pots, utensils, play food)

- Tool benches with realistic wooden tools

- Dollhouses with simple, open-backed designs and movable furniture

- Vehicle sets with ramps and roadway pieces

- Market/store setups with wooden scales, baskets, and play money

Why These Work: Role-play naturally invites interaction (“Can I cook something too?” “Let’s both be shopkeepers!”) while allowing parallel storylines.

Art and Creative Expression

- Wooden stamping sets with multiple stamps for sharing

- Simple wooden puzzles with multiple copies (2-3 of the same puzzle)

- Peg boards and pattern materials with abundant supplies

- Natural wood loose parts for open-ended creation (branches, slices, blocks)

- Wooden easels positioned side-by-side

Why These Work: Shared materials at communal tables naturally facilitate conversation and material exchange while each child creates individually.

Sensory and Exploration

- Wooden sorting and matching games with multiple sets

- Texture blocks and geometric shapes in various woods

- Musical instruments made from wood (shakers, xylophones, drums)

- Natural materials collection (smooth stones, shells, wood pieces, pine cones)

- Wooden sensory bins with tools (scoops, funnels, wheels)

Why These Work: Sensory materials are inherently engaging and discussion-prompting (“This one is bumpy!” “Listen to my drum!”) while allowing simultaneous independent exploration.

Fine Motor Development

- Wooden threading and lacing toys with multiple sets

- Pegboards with colored pegs in abundant supply

- Simple wooden bead mazes and manipulatives

- Stacking rings and nesting toys in natural wood

Why These Work: Fine motor activities allow children to work independently at their own pace while seated together, creating opportunities for observation, imitation, and conversation.

Educator Strategies That Foster Associative Play

Model Without Directing

Join play occasionally to demonstrate sharing language and social interaction, then gracefully exit to allow peer-to-peer interaction. Effective modeling phrases include:

- “May I borrow a block when you’re finished?”

- “I like what you’re building! I’m going to build something too.”

- “Thanks for sharing the paint with me.”

- “I notice you’re using triangles. I’m going to use rectangles.”

Narrate Social Interactions

Help children recognize positive social behaviors by narrating what you observe:

- “I noticed you shared the red paint with Emma. That was kind.”

- “You asked before taking the toy. That’s respectful.”

- “You both found a way to use the slide together.”

- “I see two builders working near each other and talking about blocks.”

This narration builds children’s awareness of their social behaviors without imposing adult control over play content.

Resist Over-Intervention

Allow minor conflicts to unfold naturally. Children develop crucial negotiation skills when they work through disagreements themselves. Intervene only when:

- Physical safety is at risk

- Emotional distress escalates beyond children’s regulation capacity

- Conflict persists beyond 2-3 minutes without resolution progress

- One child is being systematically excluded

When intervention becomes necessary, use coaching rather than solving: “What could you say to let her know you want a turn?” instead of “Give her the toy now.”

Create Mixed-Age Opportunities

When possible and developmentally appropriate, create opportunities for slightly mixed-age grouping (e.g., 3-year-olds with 4-year-olds). Research from the Bank Street College of Education shows that mixed-age settings enhance associative play by:

- Providing natural scaffolding (older children model more complex interactions)

- Reducing competition (children don’t compare themselves to exact peers)

- Encouraging leadership in older children and observation in younger

- Creating more varied play scenarios and ideas

Use Strategic Questioning to Extend Play

Without directing play content, use open-ended questions that encourage children to notice and describe their social interactions:

- “What are you and Marcus building today?”

- “How did you decide who would use which blocks?”

- “What did you notice about Lily’s painting?”

- “How are your towers the same or different?”

Celebrate Associative Play Moments

Explicitly recognize and celebrate associative play when you observe it:

- “You two have been playing together for a long time! You’re sharing materials and talking about what you’re building.”

- “I notice this whole table is using the art supplies together and making your own pictures.”

- “The sandbox has lots of children all exploring the sand in different ways.”

This recognition helps children understand the value of social interaction and builds their sense of competence.

Common Challenges in Associative Play and Evidence-Based Solutions

Challenge 1: Resource Hoarding and Reluctance to Share

What It Looks Like: A child collects all blocks of one color, refuses to allow peers access to certain toys, or becomes distressed when others approach “their” materials.

Why It Happens: Developmentally, 3-4 year olds are still learning property concepts and may feel insecure about resource availability. Some children also use material control as a social strategy when they lack verbal negotiation skills.

Solution Strategies:

- Provide abundant materials: When children see plentiful supplies, scarcity anxiety decreases

- Teach requesting language: “Can I use that when you’re done?” “May I have two red blocks?”

- Use visual waiting systems: Simple “I’m waiting” tokens children can place near desired items

- Honor temporary possession: “You can use those for five more minutes, then it will be Kai’s turn”

- Introduce turn-taking timers: Sand timers provide objective, non-threatening turn-ending signals

Avoid: Forcing immediate sharing, which can increase anxiety and possessiveness. Research from Child Development journal suggests that children who feel their possessions are respected actually share more freely over time.

Challenge 2: Exclusionary Behavior and Friendship Cliques

What It Looks Like: Children saying “You can’t play,” forming exclusive pairs or groups, or repeatedly rejecting specific peers’ attempts to join play.

Why It Happens: As children develop preferences and friendships, they may use exclusion to maintain control or express preference. Some exclusion also stems from limited social skills—children don’t know how to integrate new players into ongoing activities.

Solution Strategies:

- Establish inclusive classroom rules: “You can play” rather than “You can’t play”

- Model welcoming language: “Sure, you can build with us! Here are some blocks.”

- Teach integration strategies: “If someone wants to join, you can say ‘We’re building a zoo. What do you want to build?'”

- Create “open” and “private” play designations: Some programs use signals (open hand vs. closed hand) to indicate whether play is open to joining

Avoid: Forcing children to play together, which can create resentment. Instead, celebrate instances of welcoming behavior enthusiastically.

Challenge 3: Parallel Play Persistence Beyond Expected Age

What It Looks Like: A 4-year-old consistently engages in solitary or parallel play, showing limited interest in interaction despite proximity to peers.

Why It Happens: Individual differences in temperament, personality, and social comfort vary widely. Some children are naturally more introverted or need extended time at each play stage. For others, delayed social play may indicate developmental concerns.

Solution Strategies:

- Gently encourage without pressure: “Tell Sarah about your drawing” rather than forcing participation

- Partner with socially skilled peers: Pair the child with a gentle, socially competent peer during preferred activities

- Start with adult interaction: Build the child’s confidence through play with adults before expecting peer interaction

- Honor temperament: Some children will always prefer quieter, less socially intense play—this doesn’t necessarily indicate a problem

- Monitor for other concerns: If limited social interest is accompanied by other developmental red flags (described below), consult with specialists

When to Seek Additional Support: If a child shows limited associative play by age 4.5-5, and exhibits these additional concerns, consider developmental screening:

- Limited eye contact or unusual gaze patterns

- Minimal verbal communication or language delay

- Repetitive behaviors or intense fixations

- Difficulty with transitions or changes in routine

- Extreme distress in social situations

Resources: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)

Challenge 4: Overstimulation and Social Overwhelm

What It Looks Like: A child who was happily engaged in associative play suddenly withdraws, becomes irritable, or exhibits distress behaviors (covering ears, hiding, crying).

Why It Happens: Some children, particularly those with sensory processing sensitivities or introverted temperaments, become overstimulated by extended social interaction, noise, and activity.

Solution Strategies:

- Provide quiet retreat spaces: Cozy corners with soft seating where children can self-regulate

- Honor withdrawal needs: “It looks like you need some quiet time. You can rest in the reading corner.”

- Teach self-advocacy: Help children recognize their limits: “When you feel too noisy inside, you can take a break”

- Reduce environmental stimuli: Lower lighting, reduce background noise, simplify visual displays

- Offer parallel alternatives: Allow children to transition back to parallel play when needed without shame

Avoid: Interpreting all social withdrawal as problematic. Many children need regular “social breaks” to function optimally.

Challenge 5: Aggressive or Rough Play During Associative Interactions

What It Looks Like: Children hitting, grabbing, pushing, or using aggressive language during play interactions.

Why It Happens: Young children often lack impulse control and emotional regulation skills. Frustration, excitement, and poor communication skills can manifest as physical aggression.

Solution Strategies:

- Teach emotional literacy: Help children name feelings: “You felt frustrated when he took your block”

- Model problem-solving language: “You could say ‘I was using that’ instead of grabbing”

- Implement logical consequences: “When you hit, play time stops. Let’s take a break.”

- Ensure adequate space: Crowding increases conflict—provide 35-50 square feet per child in active play areas

- Supervise closely during transitions: Most aggression occurs during high-stimulation transition times

- Provide appropriate outlets for physical energy: Climbing equipment, outdoor time, movement activities

Avoid: Labeling children as “aggressive” or “mean.” Focus on teaching missing skills rather than punishing lack of skills.

Supporting Diverse Learners in Associative Play

Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Social Communication Challenges

Associative play can be particularly valuable for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or social communication difficulties, but it requires intentional support. Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy often uses structured associative play to build social skills gradually.

Effective Adaptations:

1. Use Visual Supports

- Picture schedules showing play sequences

- Visual choice boards for activity selection

- Social scripts showing appropriate interaction phrases

- “First-Then” boards: “First share blocks, then free play”

2. Structure with Flexibility

- Start with highly preferred activities to increase motivation (if the child loves trains, begin with wooden train sets)

- Gradually introduce less-preferred peers or activities

- Use timers for predictable transitions

- Create “play stations” with clear beginnings and endings

3. Teach Specific Social Skills

- Directly instruct on: greeting peers, asking to join play, sharing materials, taking turns

- Use social stories about associative play scenarios

- Role-play interactions before introducing real peer play

- Video model appropriate associative play behaviors

4. Celebrate Small Successes

- Acknowledge any social attempt, not just perfect execution

- Use specific praise: “You asked Sara for a block! Great asking!”

- Allow parallel play alongside associative play without pressure

- Track progress with simple data collection

5. Partner Strategically

- Pair with patient, socially skilled peers who naturally model good interaction

- Brief peers: “Alex is learning to share. If he wants a toy, he might point. You can ask ‘Do you want this?'”

- Supervise closely initially, fading support as skills develop

Resources: Autism Speaks Tool Kits

English Language Learners and Multilingual Children

Associative play provides natural, low-pressure language acquisition opportunities in multilingual classrooms. Children learn language best through meaningful interaction rather than isolated vocabulary instruction.

Support Strategies:

1. Embrace Multilingual Play

- Encourage children to use home language during play—cognitive and social benefits outweigh concerns about English-only interaction

- Learn basic phrases in children’s home languages to facilitate inclusion

- Use picture labels in multiple languages on toy storage

- Celebrate linguistic diversity: “Miguel taught us the Spanish word for ‘red’!”

2. Use Gestures and Visual Cues

- Model combining words with actions: “Pour” (while pouring), “Build” (while stacking)

- Accept non-verbal communication initially (sharing, pointing, gesturing)

- Provide picture-based choice boards for activity selection

- Use materials that don’t require language for successful play

3. Pair with Language Buddies

- Match English language learners with socially skilled, patient English speakers

- Avoid overwhelming with too many simultaneous peer interactions initially

- Create small group (2-3 children) play opportunities before large group

4. Use Repetitive, Simple Language

- Model simple play phrases children can replicate: “My turn,” “Can I have one?” “Thank you”

- Repeat key vocabulary during play: “Block. Big block. Stack the blocks.”

- Use songs and rhymes with repetitive phrases during transition times

5. Provide Comprehensible Context

- Choose activities where context makes meaning clear (water play, building, art)

- Use real objects and concrete materials rather than abstract concepts

- Demonstrate before expecting participation

Research from WIDA (World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment) emphasizes that language develops best through authentic communication—associative play provides exactly this context.

Children with Physical Disabilities and Motor Challenges

All children deserve access to associative play regardless of physical abilities. Universal Design for Learning principles guide inclusive classroom setup.

Inclusive Practices:

1. Adapt Materials and Furniture

- Provide materials accessible from various positions (seated, standing, wheelchair)

- Offer adaptive grips and tools (enlarged handles, specialized scissors)

- Create varied activity heights (floor play, low tables, standing easels)

- Position materials within reach of all children (avoid high or distant storage)

2. Select Universally Designed Toys

- Choose large wooden blocks easier to grasp than small pieces

- Provide magnetic or Velcro connections as alternatives to stacking (reduces frustration from falling structures)

- Offer push-pull toys requiring minimal fine motor precision

- Select open-ended materials usable in multiple ways regardless of physical ability

3. Modify Activity Expectations

- Focus on participation rather than product: success = engagement, not specific outcomes

- Allow alternative ways to contribute: verbal suggestions, pointing, directing peers

- Celebrate diverse contributions: “Maya told us where to put the block, and Eli placed it!”

4. Create Peer Understanding

- Read age-appropriate books about different abilities

- Model respectful language: “Alex uses a wheelchair to move around” (matter-of-fact, not pitying)

- Facilitate peer assistance naturally: “Can you hand that to Jordan?” (not singling out or over-helping)

Resources: National Center for Learning Disabilities

Connecting Associative Play to Educational Philosophies

Montessori Approach and Associative Play

While Montessori education emphasizes individual work and self-directed learning, associative play aligns perfectly with several Montessori principles:

Grace and Courtesy: Associative play provides authentic contexts for practicing polite social interactions—asking permission, waiting for turns, offering help.

Freedom Within Limits: Children choose their activities and approach (freedom) while learning to respect shared space and materials (limits).

Prepared Environment: Montessori’s carefully organized spaces facilitate associative play by providing clear activity areas and adequate materials.

Observation-Based Teaching: Both Montessori philosophy and associative play support rely on teacher observation rather than direct instruction.

Reggio Emilia Approach

Associative play embodies core Reggio Emilia principles:

Child as Protagonist: Children direct their own learning through self-chosen associative play activities.

Environment as Third Teacher: Thoughtfully designed spaces facilitate peer interaction and material exploration.

Documentation: Photo and narrative documentation captures learning processes during associative play.

Emergent Curriculum: Teachers observe associative play to identify children’s interests and design extensions.

Social Construction of Knowledge: Children learn through interaction with peers, exactly what associative play provides.

Waldorf Education

Waldorf’s emphasis on imaginative, unstructured play with natural materials naturally incorporates associative play:

Natural Materials: Waldorf’s preference for wooden toys and natural materials supports open-ended associative play.

Extended Free Play: Waldorf programs typically provide 45-60 minute free play periods, ideal for associative play development.

Imitative Learning: Children observe and imitate peers during associative play, central to Waldorf’s developmental approach.

Minimal Adult Direction: Waldorf teachers serve as models rather than play directors, allowing authentic peer interaction.

Family Engagement: Extending Associative Play Beyond the Classroom

Communicating with Families About Play-Based Learning

Many families, particularly those from cultures emphasizing academic preparation, may question why their preschooler “just plays” rather than engaging in formal instruction. Effective communication builds understanding and partnership.

Sample Parent Communication:

“Dear Families,

You may notice your child talking about ‘playtime’ at school. Play is not simply fun—it’s how young children learn most effectively! This month, children are developing associative play skills, meaning they’re learning to:

- Share materials with friends

- Communicate their ideas to peers

- Solve problems when conflicts arise

- Build empathy by noticing others’ feelings

These skills directly support later academic success in reading, math, and science. Research shows children who engage in rich social play demonstrate stronger school readiness than those who focus only on academic skills.

You can support associative play at home by:

- Arranging playdates with peers

- Providing open-ended toys like building blocks and art supplies

- Allowing children to work through minor conflicts before intervening

- Asking about your child’s play: ‘Who did you play with today? What did you build?’

We’ll share photos and observations of your child’s play development throughout the year.”

Home Activities Supporting Associative Play

Playdate Guidelines for Parents:

- Invite 1-2 peers (not large groups)

- Provide adequate materials to reduce conflict

- Set up activity stations (art table, block area, dramatic play)

- Supervise from a distance, intervening only when necessary

- Keep playdates short initially (60-90 minutes)

- Choose times when children are well-rested and fed

Recommended Home Materials:

- Basic wooden block sets

- Art supplies (crayons, markers, paper, play dough)

- Pretend play items (play kitchen, dolls, dress-up clothes)

- Outdoor toys (balls, riding toys, sand/water toys)

- Simple board games for transitioning to cooperative play

Supporting Associative Play in Public Spaces

Playground Strategies:

- Arrive during moderately busy times (not empty, not overcrowded)

- Allow your child to observe before joining play

- Model friendly greetings: “Can my child play too?”

- Stay nearby but resist hovering

- Let children navigate minor conflicts independently

Library Story Time and Community Programs:

- Choose programs encouraging interaction (not just passive listening)

- Arrive early so your child can ease into the social environment

- Follow up at home: “I saw you sitting next to Mia at story time. Did you like the same books?”

Safety Considerations During Associative Play

Supervision Strategies

Active Supervision Principles:

- Position strategically: Stand where you can see all play areas simultaneously

- Scan constantly: Shift visual attention every 15-30 seconds

- Listen actively: Tune into conversation tone and content

- Know your children: Understand individual children’s typical behaviors to recognize when something is “off”

- Count frequently: In large groups, count children regularly to ensure all are accounted for

When to Intervene: ✓ Physical safety risks (climbing unsafely, throwing objects) ✓ Emotional distress escalating beyond self-regulation ✓ Persistent exclusion or bullying behaviors ✓ Property destruction ✓ Conflicts continuing beyond 2-3 minutes without resolution progress

When NOT to Intervene: ✗ Minor disagreements children are actively negotiating ✗ Temporary frustration or disappointment ✗ Turn-taking conflicts where children are problem-solving ✗ Different play styles or preferences (as long as all children are engaged)

Material Safety

Wooden Toy Safety Standards: All classroom materials, should meet:

- ASTM F963 (American Society for Testing and Materials toy safety standard)

- CPSIA (Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act) compliance

- Non-toxic finishes: Natural oils, beeswax, or water-based non-toxic paints

- Smooth surfaces: No splinters, sharp edges, or rough areas

- Appropriate sizing: Follow age recommendations to prevent choking hazards

- Durability: Materials that withstand repeated use without breaking into small parts

Regular Safety Checks:

- Inspect toys weekly for damage, splinters, or loose parts

- Remove broken items immediately for repair or disposal

- Ensure adequate lighting in all play areas

- Maintain clear pathways between activity areas

- Secure heavy furniture and shelving to walls

Conclusion: Creating Environments Where Social Development Thrives

Associative play represents far more than children simply playing near each other—it’s the critical bridge between solitary exploration and true collaboration. This developmental stage lays foundations for lifelong social competence, emotional intelligence, collaborative abilities, and academic success.

As early childhood educators and administrators, our role is to:

✓ Design thoughtful environments with appropriate space, materials, and time for associative play to flourish

✓ Select high-quality, open-ended materials that invite interaction without prescribing use

✓ Observe carefully to understand each child’s social development and provide individualized support

✓ Resist over-intervention allowing children to develop negotiation, problem-solving, and conflict resolution skills through authentic experience

✓ Celebrate social milestones helping children recognize their growing competence as social beings

✓ Partner with families building understanding of play’s educational value across cultural contexts

✓ Honor individual differences in temperament, developmental timing, and cultural background

When we create environments that truly support associative play, we give children tools that extend far beyond the preschool years. We help them become empathetic communicators, creative problem-solvers, and confident collaborators—skills that serve them throughout education, careers, and relationships.

The wooden blocks they stack today teach them to build bridges with others tomorrow. The paint they share prepares them to share ideas. The conflicts they navigate develop skills for navigating life’s challenges. This is the power of associative play.

BROWSE OUR COLLECTIONS REQUEST INSTITUTIONAL PRICING DOWNLOAD OUR CATALOG